Olympic soccer powerhouse Karina LeBlanc on finding her voice

How does a timid, quiet girl morph into a sport legend and one of the strongest and most influential voices in women’s athletics?

Karina LeBlanc, head of women’s soccer for the Confederation of North, Central America, and Caribbean Association Football (CONCACAF), sparkles with confidence, energy, and enthusiasm. She has inspired international change with her powerful and passionate advocacy for girls in sport.

She was not always this way.

Meet Karina LeBlanc

Karina LeBlanc is a two-time Olympian who won a bronze medal in soccer in 2012, Canada’s first-ever medal in the sport. Read her tips for sports parents here.

“I was the shyest girl in the world,” she insists. “Nobody believes me, but ask my mom. It’s true.”

Her explanation of the transformation is simple:

“Sport is a game changer. Sport made me who I am today. This is why I am so passionate about what I do. Once I found my confidence through sports, I was telling everyone: I was going to be an Olympian. You couldn’t shut me up. I didn’t even know what sport, just I am going to be an Olympian!”

LeBlanc grew up in the Caribbean, where girls didn’t have access to many sports other than ballet and swimming. When she moved to Canada at age eight, she first embraced track and field and then basketball.

“I loved basketball. At the time, there was no WNBA. I’d tell everyone: I’m going to be in the NBA one day.”

At age 11, she followed her friends to soccer. “Soccer changed my life. What some people fail to understand is when it comes to girls and sports, the social aspect gets girls into the game and keeps girls in the game. I only did soccer because I wanted to be around my friends.”

Confidence through connection

LeBlanc says that sport gave her a way to connect with people. She remembers arriving in Canada with a strong accent that made her feel different from everyone around her. “Plus, I was the only Black kid in my school. There was nothing that connected me to my peers.”

Being on a team—having teammates with shared goals, with mutual successes and failures—allowed her to connect with the children at her new school.

“Something as simple as a high-five… how powerful and impactful is that for a young kid? Once you have connection, the confidence comes.”

Because of her athletic success, LeBlanc found her voice at 12 or 13, the very age the majority of girls quit sport. “And I don’t think I’ve been quiet for a second since,” she says with a laugh.

Confidence through failure

At 14, LeBlanc traveled with her friends to try out for a British Columbia provincial team. She remembers being in the car with all of her closest friends. Every single one of them made the team, except for her.

On the way home, her mom comforted her while her dad seemed angry, grumbling at the steering wheel. When she asked her dad why he didn’t feel sad for her, he responded: “What are you going to do about it? Are you going to let this one person determine your future?”

From that moment, LeBlanc added 15 minutes of extra training every day, either before or after practice.

“Not making that team was the best thing that ever happened to me. I learned how to find my confidence, how to work for it.”

When the next tryouts rolled around, rather than returning to the same coach, LeBlanc tried out for the age group above hers. She made the team. Within a year, she got called up to the Senior National Team and became the youngest woman on Team Canada.

“My teammates were talking about mortgages,” recalls LeBlanc, “and I was like, ‘Who am I taking to prom?’”

Despite the difference in conversational focus, LeBlanc and her peers shared a passion for the sport and for representing Canada. It turned out to be Karina LeBlanc’s first season of an almost 18-year career playing soccer on the national team.

Know your why

LeBlanc first qualified for the Olympic Games in 2008. She and her teammates traveled to Beijing with the intention of winning a medal.

“And … we didn’t,” she says. “That first Olympics, I got a picture with everybody. LeBron James. I had lunch with Serena Williams. Usain Bolt. Kobe Bryant. All the big names. I can’t tell you where any of those pictures are, but I can sure tell you where the (2012) medal is.”

LeBlanc knows exactly why the 2012 experience ended more successfully than the 2008 one. John Herdman stepped into the coaching role and asked: “Who are you and why are you here?”

The Canadian women’s soccer team had to figure out their why.

“Our why,” LeBlanc explains, “was to inspire the next generation. We created a culture and an environment where every action was tied to that why.”

At the Olympics, the Canadian team lost to the U.S. That game broke them. They felt like they’d failed and let their families and country down. Then the coach presented them with a video. “The prime minister was on that video: ‘Hey, we watched your game. We want you to bring home bronze.’ We realized people are watching.”

The video showed bars packed with fans. There were young women and men yelling, “Bring home the medal!”

That video got the team so fired up that Canada beat France, arguably the better team, to earn the country’s first ever spot on an Olympic soccer podium.

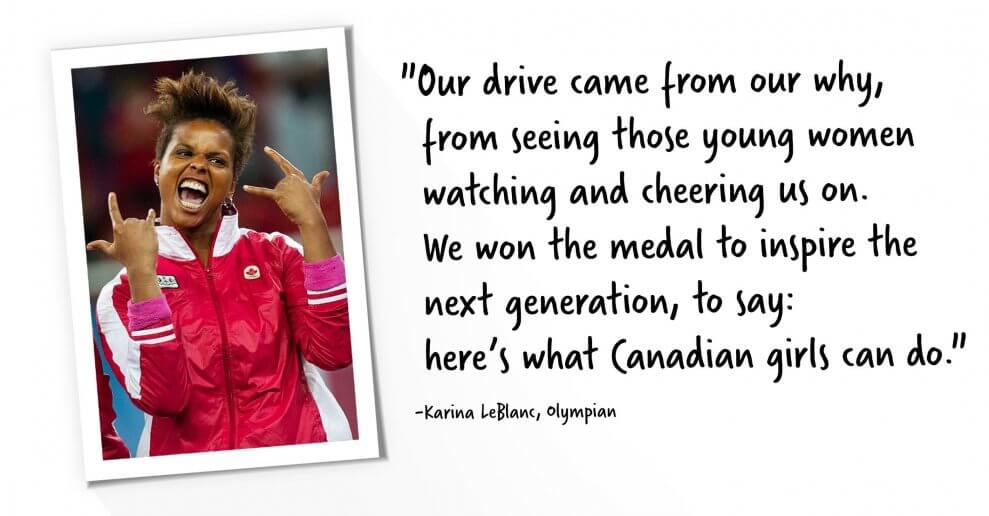

“Our drive came from our why, from seeing those young women watching and cheering us on. We won the medal to inspire the next generation, to say: here’s what Canadian girls can do.”

See it to believe it

After the 2012 Olympics, John Herdman pulled LeBlanc aside with the dreaded ‘We need to talk.’

LeBlanc assumed he had some critique of her game. She was wrong, and today, almost 10 years later, his words still ring clear in her mind: “If you think your purpose on earth is to kick a soccer ball for Canada, then I’ve failed you.”

“That rocked me,” LeBlanc remembers. “I thought, what are you talking about? I’d been playing for the country for 14 years at that time. I absolutely thought that was my purpose.”

Herdman’s question set LeBlanc on a journey to find a new why.

Ultimately, that exploration led her to her current role with CONCACAF. She’s grateful to administrators in the organization who saw something in her she didn’t see in herself. They empowered her to believe that her voice, her experience, and her leadership in women’s football could have a positive impact.

Thanks to their belief and guidance, LeBlanc now works to give girls throughout North America, Central America, and the Caribbean islands access to sport so they too can develop their confidence and find their own voices.

The main thing these girls need? Role models who demonstrate what’s possible. “If they see it, they can believe it.”

CONCACAF helps create more meaningful soccer games for girls and women. It also creates coaching education courses to get more women coaches and builds an ecosystem that allows more home games in countries where young girls have never seen women compete at this level.

Sometimes even the smallest offerings make a big difference. After one of the soccer clinics CONCACAF offers, they send each girl home with a soccer ball. “Now these girls don’t have to fight their brothers to play.”

“It’s more than sport,” LeBlanc explains. When girls can play, when they feel powerful, when they have fun, and when they establish real connections, they eventually realize that their voices matter.

“All through a ball,” LeBlanc says with a smile. “We’re not just talking about soccer anymore. We’re talking about social change.”

Three tips for sports parents from Olympic medalist Karina LeBlanc:

1. Emphasize fun in sport because fun creates memories and lasting friendships.

Children are in sport for the social time. Without her friends’ interest in soccer, LeBlanc may never have ended up in the sport.

She argues that girls particularly—up to 70 percent of them—do sport simply because of the social aspect and too many girls quit organized sport when they become teenagers.

By keeping sport fun and emphasizing the social component, we can keep more girls in sport longer and make it a safer space to help them build confidence and find a support network for those tough transitional years.

2. Remind young athletes of the many skills and assets they gain in sport.

John Herdman changed LeBlanc’s life by nudging her onto her post-sport journey. “It comes down to people opening the doors for athletes like me, recognizing the tools that we gain as high-performance athletes.”

Through sports, people learn leadership, teamwork, goal-setting, work ethic, discipline, confidence, and resiliency. Parents and coaches can help their young athletes be aware of the strengths they gain in their sport experience and think about how to apply these assets outside of the sporting arena.

LeBlanc sees Herdman as an exceptional coach and leader. He understands that the ultimate value of sport has little to do with wins and losses. “Someone asked him, ‘What’s your legacy?’ He answered, ‘That these 18 women go on to do amazing things beyond the game.’”

3. Ensuring your young athletes feel seen and heard every day will help them find their own confidence and voice.

LeBlanc and her husband both played soccer for Canada so everyone assumes their daughter will be a genius soccer player. LeBlanc simply wants to do what makes her daughter happy. “We have balls all over the place,” she says with a smile, “and our daughter loves it.”

But she has no fixation on the idea of her daughter turning into a soccer star. “If she says ‘I don’t want to play soccer,’ that’s fine. We just want her to feel seen and heard every single day of her life. If sport is the thing that helps her do that, perfect. If it’s piano, perfect. If it’s art, perfect.”

LeBlanc says the most powerful experience of her life was having the freedom and opportunity to find her own voice. She wants her daughter to have the same chance: “Our job is to make her feel safe and make her understand the greatness she has within her.”

Read more about Canadian Olympians:

Wrestling the sisterhood: Olympic gold medalist Carol Huynh on inclusion and camaraderie

How failure builds resilience: Insights from Olympian Neville Wright

The power of self-discovery: Tips for parents from Olympian Martha McCabe

Leadership lessons: Olympic gold medalist Adam Kreek on how youth sport builds successful adults