Leadership lessons: Olympic gold medalist Adam Kreek on how youth sport builds successful adults

As a child, Adam Kreek didn’t even like sports.

He came from an athletic family, with a dad who coached basketball and a legendary grandfather who’d won a gold medal in shotput at European championships, but Kreek actually preferred music lessons.

“I went to a small school, which pushed me toward sport,” he says. “The teachers needed every boy to play in order for there to be a team. So I played soccer, basketball, and then in high school some American football and shotput.”

Meet Adam Kreek

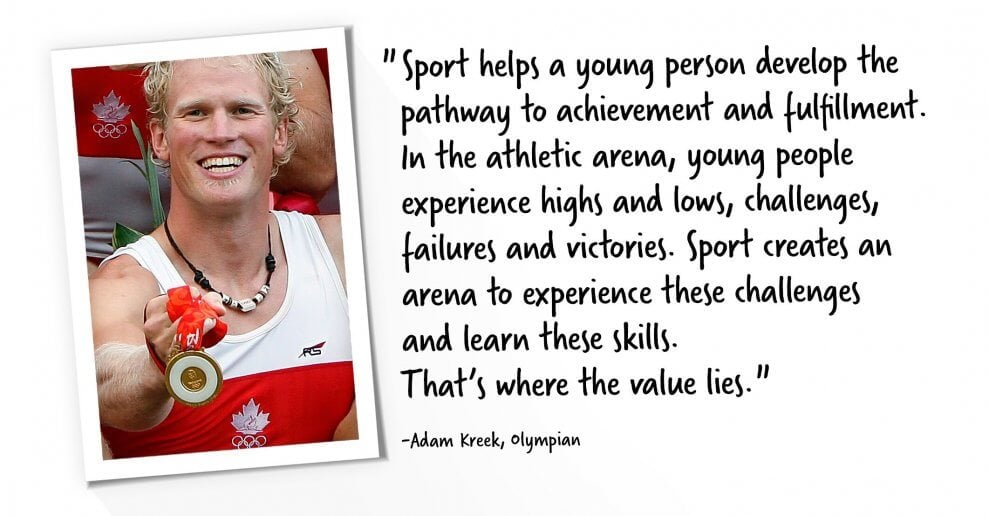

Adam Kreek is a two-time Olympian who won a gold medal in rowing in the men’s eights event in Beijing in 2008. Read his tips for sports parents here.

As Kreek—a tall and muscular youth—became successful in athletics, he still never put much value in sport itself. “Sport was an avenue for exercising potential, practicing discipline, seeing the world.”

Even now, as an adult and Olympian, Kreek argues that the most important lessons of sport have very little to do with sport for sport’s sake.

Kreek worked hard and he got better; that progression (and the friends he made along the way) encouraged him to stick with the athletic challenge. “I liked being with people and developing those kinds of connections you make through the challenge of sport.”

Right coaches at the right time

Because Kreek didn’t like ball sports, his parents sent him to mixed sport camps in the summer, such as the “sport smorgasbord” camp at Western University. They kept encouraging him to try different athletic activities, hoping one might catch his interest.

In Grade 11, Kreek happened to attend the same school as the daughter of Walter Benko, coach of the London Rowing Club. Benko and co-coach Peter Carson encouraged Kreek to come out for the rowing team.

“I was playing football in the fall, basketball in the winter, and thought, well, I guess I’ll do rowing in the spring.”

Despite Kreek’s quick success, Benko and Carson didn’t rush to capitalize on his potential. Instead, they told him: “Don’t push too hard.”

In a sport that depends on power and endurance, men don’t peak until 28 to 32 years old. “Push later,” Kreek recalls his coaches saying. “Too many young athletes burn out too soon. Enjoy being fit. Enjoy the competitive spirit. The rowers who beat you now will not last to be the ones who beat you later.”

Looking back, Kreek appreciates having coaches who tempered his enthusiasm, led him to a clarity of vision, assisted him in using that vision to establish healthy priorities, and set him up for long-term success.

Coaches as leaders

As an Olympian, Kreek worked with coach Mike Spracklen, who won a medal in rowing at every Olympics from 1984 to 2012.

Spracklen’s training schedule was grueling. Kreek and his teammates committed to 50 weeks of hard physical work per year, with just two weeks off after every world championships. They did 18 training sessions per week with five to seven hours of workouts per day. To fuel this output, they needed to consume between 8,000 and 12,000 calories every day. They also had to find time to do the four loads of daily laundry created by this regime.

“It was an intensely structured existence,” Kreek says.

He remembers waking up at 5:30 each morning with every single one of his waking hours accounted for, knowing he would repeat the same routine day after day, week after week, month after month.

How did Spracklen inspire that kind of dedication and discipline in his athletes?

“Spracklen embodied excellence and the competitive spirit, and he didn’t make anyone do anything,” Kreek recalls. Instead of making demands, Spracklen asked well-timed questions. Do you value the process? What is your end game? Will you commit your all to get there?

“If your goal was to win an Olympic gold medal, Spracklen would coach you. If you simply wanted to have an Olympic experience—to go to the Games and get the T-shirt—that’s a perfectly acceptable expectation too, but you’d have to find a different coach.”

As a leader, Spracklen set the path, created a winning training program, and then athletes had to choose for themselves whether to take that path. He used questions and challenges to motivate his athletes, but never orders.

Sport’s lessons in leadership

When immersed in his athletic career, Kreek would not have been able to define leadership. He didn’t become consciously aware of leadership as an idea until after his Olympic experience.

“We had no leadership training in school. Nobody talked about leadership. I can define it now, though. Leadership is: one, having a very clear vision as to what you want an outcome to be, and two, knowing how to enlist other people to help you achieve that outcome.”

Kreek stresses that in his early sport experience, he learned followership more than leadership—and that too is a valuable skill. “I had to be able to follow my teammates, my coach’s program, my medical professionals’ advice, and my own inner voice,” he says.

Through rowing, Kreek also mastered self-leadership. “You have to learn to lead yourself before you lead others,” he explains.

As with any leadership, the two key components are vision and influence. Can athletes create a performance goal (a vision) and then motivate themselves to do the work required (exerting daily influence on themselves)? That is self-leadership.

A coach or parent can assist athletes toward self-leadership by asking the right questions: What do you want? What is your vision? Now what do you need to do to make that happen? Who are you going to enlist to help get you there?

Another important lesson of sport is shared leadership. Kreek likens this concept to a jazz band, with each of the musicians taking a turn at the solo. “There needs to be a tremendous amount of trust and understanding between the individuals to enact this kind of group leadership, but when it works you can experience a sense of joyful euphoria and enlightenment as part of a functioning team.”

The jazz band analogy works well to capture Kreek’s Olympic gold medal experience with the men’s eights in 2008. As a part of a high-performing team, Kreek recalls being able to rely on his teammates to pull him through his moments of doubt. “Every one of us knew we were going to win at a different moment of the race.” Each rower became the leader in his own moment of confidence.

Why sport?

“What is the purpose of sport? I think everyone wonders that,” Kreek says with a laugh. “Don’t they? I mean, why all that effort to go a half a second faster in a swimming pool? Pretty esoteric pursuit.”

Kreek has spent much time reflecting on this question, both through his executive coaching and training practice, KreekSpeak Business Solutions, and while writing his first book, The Responsibility Ethic.

“Sport,” he says, “helps a young person develop the pathway to achievement and fulfillment. In the athletic arena, young people experience highs and lows, challenges, failures and victories.” Without sport, they might not have such experiences until their 40s or 50s as leaders of organizations.

“Imagine leading 50 or 100 or 1,000 people,” Kreek says. “Imagine this is your first time with highs and lows, with stress, with needing grit, with requiring extreme effort. Imagine this is your first time having to create a vision and bring other people toward achieving it. Sport creates an arena to experience these challenges and learn these skills. That’s where the value lies.”

For Kreek, the true benefit of sport comes in the leadership lessons it teaches young people and the way those athletes can then apply these skills to their adult experiences of being teachers, doctors, firefighters, lawyers, carpenters, or whatever they choose to be.

Three tips for sports parents from Olympic gold medalist Adam Kreek:

1. Expose your children to as many opportunities as possible. You never know what will build skill and spark interest.

As a child, Kreek enjoyed band more than sports. The lung capacity required to play the tuba and the trumpet helped him when he made the switch to rowing.

What sparked his initial interest in rowing? “I used to go on canoe trips with my dad. I really liked that.”

After high school, he took a year off to work physical labour on oil rigs. “That was hard. Cold, muddy, wet, and guys swearing at me. None of it very nice. That kind of experience teaches you fast: life is hard.” The grit he learned in the workforce served him well when he turned his attention to the full-time task of training to be an Olympic gold medalist.

2. Be sure athletic goals are child-driven, not parent-driven.

Kreek now has three children and takes a very laissez-faire approach to his role as a sport parent. Following the lead of his Olympic coach Mike Spracklen, Kreek asks his children questions rather than forcing his own vision of sport on them. He finds out what his children want and then helps them set their own path.

With reference to Andre Agassi’s memoir Open, Kreek emphasizes the damage that comes from parents pushing their children or living out their own unrealized dreams in youth sports.

“We want sport to be a nurturing force in our society,” he says. “We don’t want sport to be an activity that creates more psychological trauma.”

3. Teach children to harness their nerves.

One aspect of self-leadership is learning to manage the intense emotions that come with competition. Kreek recalls Spracklen telling him: “Well, Adam, you’re not going to win an Olympic medal without being nervous.”

A mother bear summons the strength to defend her cubs because she’s nervous. A deer runs fast enough to escape a wolf because it’s nervous. Fear motivates. “Fear makes you stronger; when harnessed, nerves have incredible power.”

Learning to use nerves in a productive way is part of sport’s education in self-leadership, a lesson that will be useful in athletes’ competitive careers but will also, and more importantly, help them throughout their adult lives.

Further reading:

Wrestling the sisterhood: Olympic gold medalist Carol Huynh on inclusion and camaraderie

How failure builds resilience: Insights from Olympian Neville Wright

The power of self-discovery: Tips for parents from Olympian Martha McCabe

7 years ago today I had the opportunity to meet you at one of the sales meetings that I was at with Trueblue when I was working for them and actually had the opportunity to hold your gold medal in my hand and chat with you for a few seconds. But more profound was hearing you talk about what it takes to become the best version of yourself and I just wanted to say “Thank you” you left a great memory in my soul, one I still carry with me today.

Excellent article Adam!